Fast urban growth is a major challenge for large cities such as Da Nang in Vietnam. It puts pressure on education systems and exhausts the capacity of state-run schools. In this article, VVOB explains a project that explores how growing up in a city affects learning and participation for preschool children, and how education needs to be adapted to address this.

Background

Rapid urbanisation creates social and spatial changes, such as less interactions among community members, and less green, open space for play which can impact children’s development. City services need to safeguard the full potential of urban development to benefit all citizens, including newcomers from rural provinces. Sustainable urban development is increasingly recognised as a key development challenge, but few organisations have dedicated programmes.

VVOB – Education for Development, a nonprofit organisation, is working with the Da Nang Department of Education and Training (DOET)to deliver the ‘Communities of practice Inspiring Teaching Innovations in the early Education System in Vietnam’ (CITIES) project from June 2019 until February 2021. The project focuses on the Son Tra District of the city, an industrial port district with many seasonal and migrant workers.

Observation

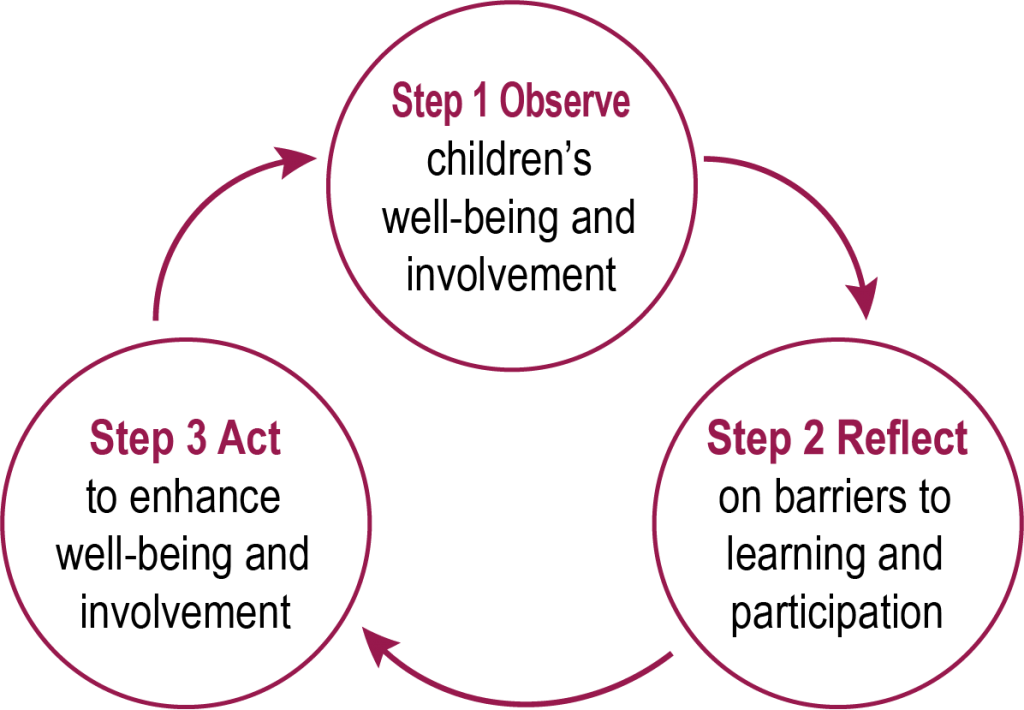

We trained teachers and government officials for 8 preschools (6 state-run, 2 private) in Son Tra district to observe and measure children’s well-being and involvement, indicators that children are learning (see diagram). We used methods including training, workshops, onsite coaching, collaborative learning and exposure visits. Due to COVID-19 social distancing measures, we delivered some training online.

The teachers and government officials identified potential barriers to learning and participation. These included teacher-led didactic methods, classes with high pupil-teacher ratios, and scarce, unattractive materials and resources. Limited parent-teacher contact was also identified as well as parental pressure on teachers and children, leading to children attending many academic extra-curricular activities and private tutoring. Beyond school, urban-specific barriers include parents working long hours and experiencing poor well-being; insufficient clean, green, safe spaces for playful learning; new technologies replacing meaningful human interactions; and changes in social relations compared to rural life – less interaction with neighbours and peers, distrust, and weakened social ties.

To address these barriers, teachers implemented 8 action points:

- Rearrange the classroom in appealing corners or areas.

- Check corners to replace unattractive materials with more appealing ones.

- Introduce new materials and activities.

- Discover children’s interests and find related activities.

- Support ongoing activities with stimulating impulses and enriching interventions.

- Widen possibilities for free initiative, support with rules and agreements.

- Explore and improve the relation with each child and between children.

- Introduce activities that help children explore the world of behaviour, feelings and values.

The child monitoring approach supports teachers to become reflective, continuously improving education quality.

By modifying preschool activities, materials, interactions, and environments, they moved away from a one-size-fits-all approach to a more differentiated pedagogical approach.

Developing creative pedagogies

We piloted an innovative methodology using applied artistic practices and interactive theatre methods to build children’s socio-emotional skills and resilience. A group of international and national artists worked with teachers to develop these methods, analyse their local relevance, and their impact on the children’s well-being and involvement.

‘Action Paint’ – children close their eyes, listen to music and feel the rhythm. They start painting using different tools. The product is not predefined, but the result of what children feel.

Providing teachers with opportunities to try out, reflect, share, and adapt these methods helped them understand the objectives of using the methods for children’s holistic development. Such approaches to teachers’ professional development go beyond cascade and knowledge driven trainings and provide teachers with opportunities to reflect on and learn from their own practice.

These pedagogies stimulate children to create, to express, and to reflect on their experiences, and they build self-confidence and create opportunities for interaction. This supports the national Ministry of Education and Training’s aims to deliver child-centred learning and learning through play. When schools reopened after COVID-19 closures, teachers commented on the benefit of using their newly developed pedagogies to welcome children back to school.

Public versus private

Due to limited public service capacity, private schools increasingly cater for disadvantaged learners in urban contexts. The project’s start-up phase revealed a difference between teaching staff in private and public schools. Private schools have more teacher turnover and less professional development, affecting the quality of education. Private schools also have less time for in-service training and participation in the project. Guaranteeing quality education for all children, however, is a core government responsibility. These initial lessons are very relevant for local government officials, as it makes them reflect on the role they can or should play.

Conclusion

Growing up in a city offers opportunities but also specific barriers to learning and participation that may increase inequalities especially for the most disadvantaged. Teachers and government officials often lack awareness of the specific challenges facing learners in urban contexts. Our small intervention created awareness of the need for specific approaches in the classroom and across the education system. It developed the capacity of teachers to apply reflective and adaptive pedagogies. In the next phase, teachers will explore how to use these opportunities to mitigate the barriers.

Contact:

Thi Chau Nguyen, Education Advisor. Email: chau.nt@vvob.org

Lieve Mieke Leroy, Education advisor. Email: lieve.leroy@vvob.org

Nguyen Dinh Khuong Duy, Project Coordinator. Email: duy.ndk@vvob.org

VVOB Vietnam, 3-5 Nguyen Binh street, Hai Chau dist., Danang, Vietnam

Web: https://vietnam.vvob.org & www.vvob.org

The authors thank Wouter Boesman, Hans De Greve, Filip Lenaerts and Ly Thi Kim Tran for contributions to this article.