Inclusion in visual workshop activities: Reflections from a blind participant

Addah Arcilla

In September 2011, EENET conducted an inclusive education workshop in Bandung, Indonesia. Workshop participants included members of national education ministries, and staff from several international nongovernmental and inter-governmental organisations. Participants came from Afghanistan, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.

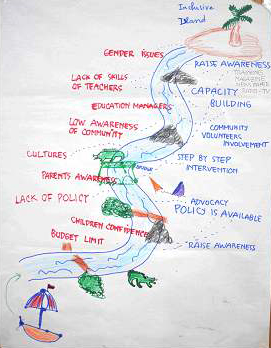

EENET has been running workshops in Africa and Asia for some years now. The workshops involve participants in drawing and photography in accessible and engaging ways. Addah has a visual impairment, and she participated in a workshop in Bandung, Indonesia. One of the group activities was to create ‘mountain diagrams’. This involved drawing a visual metaphor (a mountain with rivers and trees) to show the barriers and solutions to promoting more inclusive practice. Another involved ‘reading photographs’ – participants discuss photos taken by students and teachers in various education contexts around the world. Who has taken the photos? Why? Later, the actual details about the photos and their contexts are revealed. The planning and timing must be carefully thought out in order to make these activities as accessible and meaningful as possible. In this article, Addah offers her personal reflections on these visual activities.

Drawing mountain metaphors

Our ‘mountain diagram’ was truly a team effort because those weren’t just my drawings. They were everybody’s drawings. My group was my eyes, and I was just the hand that drew the lines.

I was confident that I’d be able to do it – but I wasn’t sure whether the other members of my group would trust me with the task. I was half expecting to be met with hesitation when I said I’d like to draw for them. Fortunately there was none of that. I took a pen and asked them what they needed; they told me where to draw, and the rest, as they say, is history. It would have been hard for me to draw some of the things if no one had told me where a line ends, or where I should put the details that would complete a picture. It felt good that I didn’t just sit there while they were all bustling over the diagram; that I actively participated in its creation.

Addah drawing a ‘Mountain Diagram’ with her group

The mountain diagram created by Addah and her group

Photo elicitation

The photo activity was not as easy as the drawing activity. I had to depend on someone to describe the photos for me. My interpretation depended on how much detail was given to me – or on the details which my interpreter found significant in the picture. One person’s description might have more details than another’s.

The time constraint also made the activity difficult for me. There were 15 photos in the batch and it takes time to describe every single detail in each picture. We could have divided the photos among us; so that two people could work on a sub-set of photos and the other two could work on another sub-set. This way we could have had more time for looking at and describing the photos.

Why did I feel so confident to draw during the EENET workshop? It’s because I expect people to trust me, and to be treated as an equal and nothing less.

Addah can be contacted at addah.arcilla@cbmseapro.org

| Addah’s story: The challenge of being a teacher with a visual impairment

Addah Arcilla I was not born blind. I became visually impaired because of profound diabetic retinopathy. I’ve had low vision since I was 23, which has slowly regressed into severe low vision due to cataract and retinal detachment. I graduated from the University of the Philippines where I took a bachelors degree in Family Life and Child Development. I am now taking my masters in Education with a specialization in Special Education at the Philippine Normal University. Before starting work at CBM, I worked as a preschool teacher for 5 years. I taught classes where children with intellectual and developmental disabilities were integrated. I was forced to give that up, not because of my deteriorating vision, but because my employers thought that I was no longer capable of teaching because of my visual impairment. I had difficulty returning to teaching because many of the schools I applied to were hesitant to take me in. I’ve always been honest about my visual impairment. When they saw me coming in with a cane or reading with a magnifier, people would always question my capability to teach and handle a class. I’ve even applied for online English teacher posts where they use VoIP software like Skype to conduct the sessions, but they were also unwilling to take the chance of employing a visually impaired tutor. I found work as a freelance web content writer for another visually impaired person who owns a business management and consultancy company. It was a drastic move from teaching very young children, but then again, it was the only job opportunity that was open to me at that time. I worked freelance in the business sector for another 3 years. I joined CBM in August 2010. While CBM may have taken me further away from teaching, it has allowed me to work on issues that confront me as a person with visual impairment, the children that I would have taught, and the disability sector in general, albeit not in a direct way. Work is very challenging in CBM, not because I am confronted with prejudices but because it’s a new field for me and because of the enormous responsibility that comes with the job. For that I am glad because I am treated as an equal among my peers. |